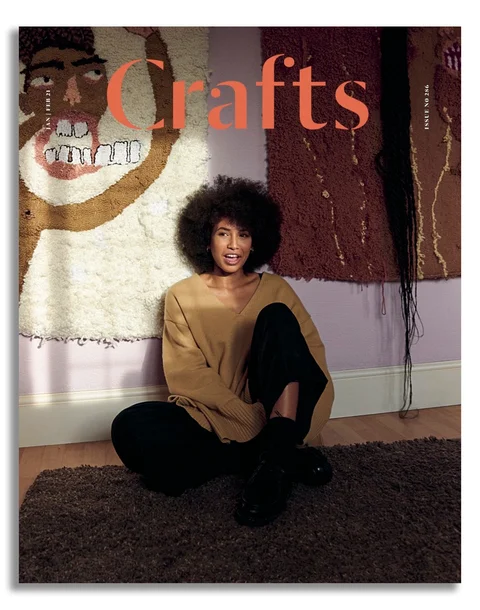

Magdalene Odundo, photographed in her studio. Photo: Alun Callender / Crafts magazine

I am an urban being, but very occasionally I long for walks through woods and over fields. I hanker after those Sunday afternoon drives down bramble-banked lanes, through one-road villages to ancient market towns – perhaps to gather by the glowing hearth of a black-beamed pub.

But this was a different kind of country expedition. On this morning in late 2020, I was driving west out of London for an encounter even more warming and comforting. I was on my way to see one of the greatest living ceramicists: Magdalene Odundo. A friend but somehow someone that I hadn’t seen for more than a decade. Although life had seen our paths diverge, I had followed Magdalene’s successes through the newspapers, visited her exhibitions and celebrated her prizes and plaudits from distance – and felt a vicarious fist-pumping pride at news of her damehood this year.

She had earned that love and respect over decades of teaching, championing the sector and producing exquisite ceramics. Odundo’s pots are rendered with an uncanny, unearthly precision, unreal in their perfection, exuding a sense of being born, of being nurtured into the world rather than made.

Untitled, by Magdalene Odundo, 1987, burnished and carbonised terracotta. Courtesy: the artist and Anthony Slater-Ralph. Private collection. Photo: Phillips

Untitled, by Magdalene Odundo, 2000, burnished and carbonised terracotta. Courtesy: the artist and Anthony Slater-Ralph

Pulling into her drive, I was excited to see her, to see what she was working on, to hear her news. But even silhouetted within the door frame, there seemed to be something about her that suggested that things were not quite right. Her greeting was as warm and lovely as ever, but there was the shadow of something else. I wanted to hug her, but COVID-culture forbade it. I wanted to ask, but my courage escaped me. Then over lunch she began – ‘I have been unwell ….’

It was an illness that had forced her to spend months in hospital, some of it gravely ill. Even as it retreated from her body, it lashed out, threatening her motor functions, and even months into recovery it continued to compromise her dexterity and finger sensitivity – the most vital tools in a potter’s arsenal.

But it was at her most physically vulnerable that she was reminded of the power of her practice. We all know those stories of how creative compulsion can drive artists – we know about Turner lashing his body to a ship’s mast to capture the visceral intensity of a storm on canvas; or Ibrahim El-Salahi risking his life to clandestinely make work on the discarded cigarette packets of his guards while incarcerated in the notorious Kober Prison in Khartoum. We know the drive to create is fundamental. But this was something else, not a railing at the world, not an urge to make art at any cost, but an even more elemental desire, simply a need to make to be.

Odundo’s pots are rendered with an uncanny, unearthly precision, unreal in their perfection, exuding a sense of being born, of being nurtured into the world rather than made

Gus Casely-Hayford

Odundo spoke of making as spiritual sustenance, necessary for life, of the creative instinct being an existential catalyst – a force for engendering well-being. For her, making is deeply recuperative. And when you look at her practice – how it conjures its visual language from some deep, shared place of solace and succour – you understand how, after years of investing in a bank of such beauty, it would repay when she needed it.

Untitled pair of vessels, by Magdalene Odundo, 2013, burnished and carbonised terracotta. Courtesy: the artist and Anthony Slater-Ralph. Private collection

Untitled, by Magdalene Odundo, 1986, burnished and carbonised terracotta. Courtesy: the artist and Anthony Slater-Ralph. Private collection. Photo: Phillips

My journey home was fuelled by the inspiration of the afternoon, musing on Odundo’s strength, on her talent and her work. For some, like her, to create is not a choice: it is an existential need. And, in this time of global recovery and reflection, as resources tighten and humanity itself tries to regain its strength, museums and galleries also play a necessary role in recuperation, as spas for the soul. They are spaces where we can enjoy the most glorious manifestations of that fundamental human drive to make, to create, to build, to be.

Making is the driver of our earliest intelligent compulsions. Before we walk and talk, we exhibit a desire to make, to craft, to construct – and that compulsion links cultures across geography and history. It unites and makes sense of us, and when fate threatens us, it could be our life raft. From the work of our most lauded artists to our earliest daubs, to the manufacturing and creative sectors that underpin our economy, making underwrites who and what we are.

This article first appeared in Crafts' January/February issue