Itō Sekisui V is carrying on a family business in ceramics that has been going for centuries on the island of Sado. He uses the same local mumyōi clay—rich in iron oxide, which gives it a gorgeous red color—as have generations of his predecessors. Yet his innovative techniques have given the art fresh life.

The ceramic artist Itō Sekisui V was born and raised on the island of Sado. How does he feel about his home? “To put it briefly, I take this land very seriously,” he says.

Itō Sekisui V was designated a living national treasure in 2003.

Itō Sekisui V was designated a living national treasure in 2003.

Itō Ihei, an ancestor of the “living national treasure” Sekisui, moved to Sado from the mainland around the time of the 1640 gold rush, when the island’s gold and silver mine was flourishing. His son Jinbei built a kiln and started making the bellows and tuyère pipes used in gold smelting, as well as unglazed ceramic items for everyday use. Through the generations, the family came to produce more sophisticated tea bowls and plates. In the nineteenth century, a kind of red clay called mumyōi was discovered in the gold mine. Itō Tomitarō, the ninth generation of the family that started with Ihei, fired the clay at high temperatures to create the ceramic style known as mumyōi-yaki. Shortly after the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Tomitarō took the name Sekisui, which has now been passed down for five consecutive generations.

Today’s Sekisui V has deep roots in Sado, and the family has produced ceramics for centuries.

“It’s continued for so long—thirteen generations—that I can’t quit today. Both mumyōi-yaki and Sado are heavy presences for me.”

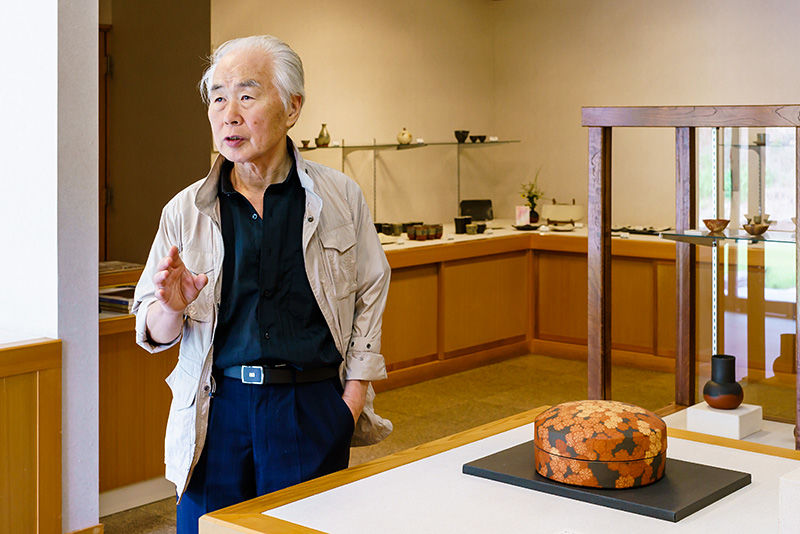

A room with works by Sekisui V in the Itō Sekisui Museum, which displays art by all five generations sharing the name.

A room with works by Sekisui V in the Itō Sekisui Museum, which displays art by all five generations sharing the name.

Beautiful “Failures”

Mumyōi, red clay taken from near the veins of the mine, is rich in iron oxide. It has long been used in China as a traditional medicine for stanching bleeding. In Japan it is only found near the Sado gold mine as a byproduct of mining. If fired at high temperatures, it becomes very hard, giving off a clear, metallic sound when struck.

A sign reading 無名異坑 (mumyōi mine) near the entrance to the remains of the Sado gold mine.

A sign reading 無名異坑 (mumyōi mine) near the entrance to the remains of the Sado gold mine.

“In Chinese traditional medicine, iron is an important element, and it is particularly abundant in mumyōi,” Sekisui says. “The clay feels dry like sand. Some forms of ceramics use clay with stones containing radium. Perhaps when they first made mumyōi-yaki, they were seeking to achieve a similar kind of medicinal effect.”

Early mumyōi-yaki works by Sekisui V.

Early mumyōi-yaki works by Sekisui V.

Sekisui V was born as Itō Yōichi in 1941. Before he entered university, his father died. This meant that he learned the art of making mumyōi-yaki from his elderly grandfather Sekisui III. Forced to immerse himself in the family trade at a tender age, he started work in earnest in 1966. Japan’s economy was booming, as was the Sado tourist industry. Mumyōi-yaki items were highly popular in the island’s tourist shops, but Yōichi did not get carried away by this, setting his sights on reaching a higher level as an artist.

Mumyōi-yaki is known for its gorgeous red color. Yōichi’s predecessors valued a beautiful red that calls to mind Chinese-style shudei (vermilion earth) works. However, the high level of iron oxide in mumyōi-yaki means that it turns black where it is touched by the flames in the kiln. This yōhen wood-firing effect was traditionally considered to result in a failed piece, but Yōichi thought that burning some parts black might set off the red to greater effect. Using the yakishime technique of firing unglazed wares at extremely high temperatures, he created his own distinctive series with a striking contrast between the two colors.

The eye-catching contrast of red and black is the keynote of the yōhen series.

The eye-catching contrast of red and black is the keynote of the yōhen series.

“Depending on where potters place the works in the kiln, they can have a good idea of what kind of yōhen will happen,” Sekisui says. “However, it is not possible to do this with a precise level of control over the outcome. This is the interesting thing about pottery. With the color changes, I’ve added range to my work.”

Sekisui offers insight into his works.

Sekisui offers insight into his works.

Breaking New Ground

Following the creation of his innovative two-color series, in 1972 Yōichi had his first work accepted for inclusion in the annual exhibition of the Japan Kōgei Association, which supports traditional crafts. His reputation grew, and in 1977 he became the fifth in his line to take the Sekisui name. However, he still sought to break new ground. His next challenge was to knead together different colors of clay, a technique known as neriage, so as to produce a pattern. In 1985, his mumyōi works in this style won the Grand Prize and Prince Chichibu Cup at the Japan Ceramic Art Exhibition.

His early neriage pieces were simple patterns based around lines. Today he has advanced to flowers, fish, and birds, created by layering clay so it looks something like rolled sushi, cutting through it, and lining up the cross-sections.

A flower-patterned neriage container.

A flower-patterned neriage container.

Designation as a living national treasure in 2003 did not slow him down either. In 2009, he applied rhyolite and granite from Sado, a volcanic island, to a new mumyōi-yaki series he called Sadogashima, after the island’s Japanese name. The use of natural minerals gave the works a rough, unsophisticated power.

The Sadogashima series uses volcanic materials.

The Sadogashima series uses volcanic materials.

Although he speaks of the heavy importance he places on Sado and his family trade, Sekisui displays a freedom and lightness in his attitude to and thinking about his creations. He is not tied by tradition and does not cater to his admirers.

“It might sound like I’m showing off a little,” he says, “but we creators trust our own sense and work on the pieces that we want to. It’s better if people ultimately accept that. My basic thinking is to create by myself. I’m not just making something; I’m creating my own work. My family has worked with mumyōi clay for generations, but within that genre it’s important for me to exercise my originality.”

Although many Japanese people refer to the island as simply Sado today, Sekisui prefers the older name, Sadogashima.

Although many Japanese people refer to the island as simply Sado today, Sekisui prefers the older name, Sadogashima.

An Island of Exile

Sekisui has exhibited overseas on numerous occasions and institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London include his works among their collections. He is still full of energy. In 2017 his solo exhibition Red Soil was held at the Onishi Gallery in New York after seven years of preparation.

The connecting flower pattern between the lid and the container displays the care that went into the work.

The connecting flower pattern between the lid and the container displays the care that went into the work.

Sekisui feels the pressure of his heritage, but seems to use it as a springboard for vigorous creativity. I ask him about Sado again and he responds, “When I think about what the island possesses to convey to the world, the answer has to be culture.

“Sadogashima has been an island of exile since ancient times. People who defied the central government were sent here, including Emperor Juntoku, the Buddhist priest Nichiren, and the playwright Zeami. But what was unusual was that they had to be self-sufficient. So long as they didn’t leave the island, they were free to marry or apply their talents to business. As a result, the manners and customs of the nation’s center were conveyed here, fostering a kind of highly cultured freedom, which took firm root. If my works have inspired any interest in Sadogashima, I would like to tell people that it is not the kind of place that you can get around and understand from a day trip alone.”

The Itō Sekisui Museum building looks down over the Japan Sea.

The Itō Sekisui Museum building looks down over the Japan Sea.

Itō Sekisui Museum

Address: 808-3 Shimoaikawa, Sado, Niigata Prefecture

Open: Every day from the second Saturday in April until November 23. Closed during winter.

Hours: 8:30 am to 5:00 pm (until 4:00 pm during some parts of the year)

Tel.: 0259-74-0011

The sign reading 赤水 (Sekisui) displays the entrance to the museum along the seaside road Route 45.

The sign reading 赤水 (Sekisui) displays the entrance to the museum along the seaside road Route 45.

(Originally published in Japanese on February 2, 2018. Reporting and text by Aoki Yasuhiro. Photographs by Miwa Noriaki.)