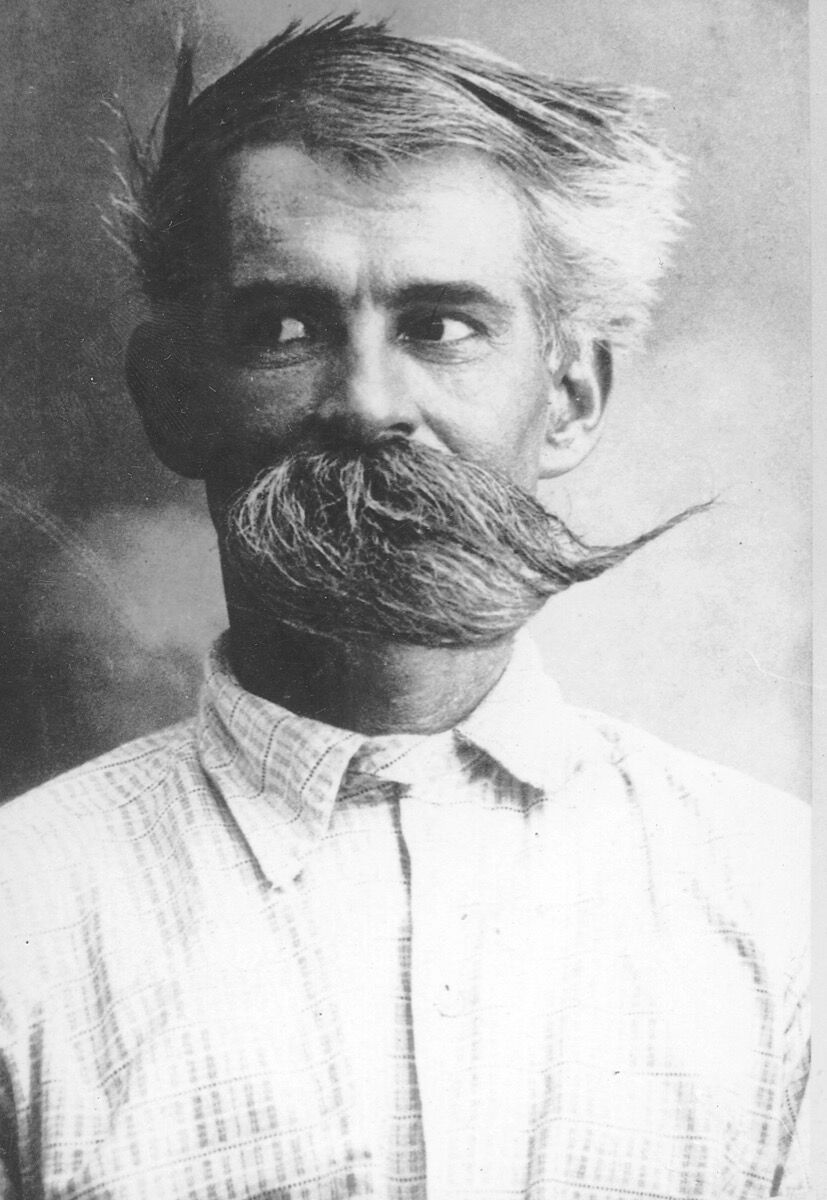

George E. Ohr. Courtesy of the Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art, Biloxi, Mississippi.

George E. Ohr, Vase, 1897–1900. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

, the so-called “Mad Potter of Biloxi,” was a wild, inventive ceramic artist in the late 19th and early 20th centuries—but his work was largely misunderstood during his time, and languished in a Mississippi garage.Ohr’s sculptural pots—writhing forms that were innovative, imaginative, and required great technical skill—were snubbed by artists of the

, the ceramics community, and the people of Biloxi alike. Despite this, Ohr pursued his work in earnest, and had the confidence and bluster to match. But it wasn’t until five decades after his death that others began catching up.

“He was 50 years ahead of his time,” says ceramics expert and art historian Garth Clark. “And the interesting thing about him was: He knew it.” In interviews and writings, the artist made it clear that he didn’t think his own generation would understand him. “When I am gone, my work will be praised, honored, and cherished,” he once said in a 1901 interview.

Today, Ohr is recognized as a major pioneer of American ceramics. He has a

-designed museum in his name, his works can be found at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Smithsonian. At auction, a large vase with handles, doused in a signature kaleidoscopic glaze, has gone for as much as $84,000.

Vase by George E. Ohr. Courtesy of the Ohr-O'Keefe Museum of Art, Biloxi, Mississippi.

Vase by George E. Ohr. Courtesy of the Ohr-O'Keefe Museum of Art, Biloxi, Mississippi.

His work has made a lasting impact on the ceramics community and the art world alike, and has inspired generations of artists working in ceramics to innovate and work with the medium in unique ways. Artists moved by his legacy include , all included in an exhibition that Clark curated at the Boca Raton Museum of Art, on view through April 8th. “Regarding George Ohr: Contemporary Ceramics in the Spirit of the Mad Potter” celebrates Ohr’s innovative spirit, joining his works with those of present day boundary-pushers.

Born in Biloxi to German immigrant parents in 1857, Ohr got his start in ceramics in New Orleans in the 1870s, where potteries were thriving (later, the city’s all-women Newcomb College would become a major hub of ceramics in the United States). At 22, Ohr was invited by a friend, Joseph Fortune Meyer, to become an apprentice at the pottery his family ran. He would later write, “When I found the potter’s wheel I felt it all over like a wild duck in water.”

After learning to throw pots in New Orleans, Ohr spent over a year traveling by train through 16 states to visit other potteries; he witnessed the state of ceramics in the U.S., and encountered peers who had begun emulating the style and techniques of French and Japanese pottery. In 1883, Ohr returned to his hometown of Biloxi and, with just $26.80 to his name (roughly $620 today), he built his own pottery, including a handmade kiln and throwing wheel, beside his parent’s house. This was the first of several studios which Ohr would later adorn with bold-lettered signs, describing himself as the “greatest art potter on Earth,” his work “unrivaled.”

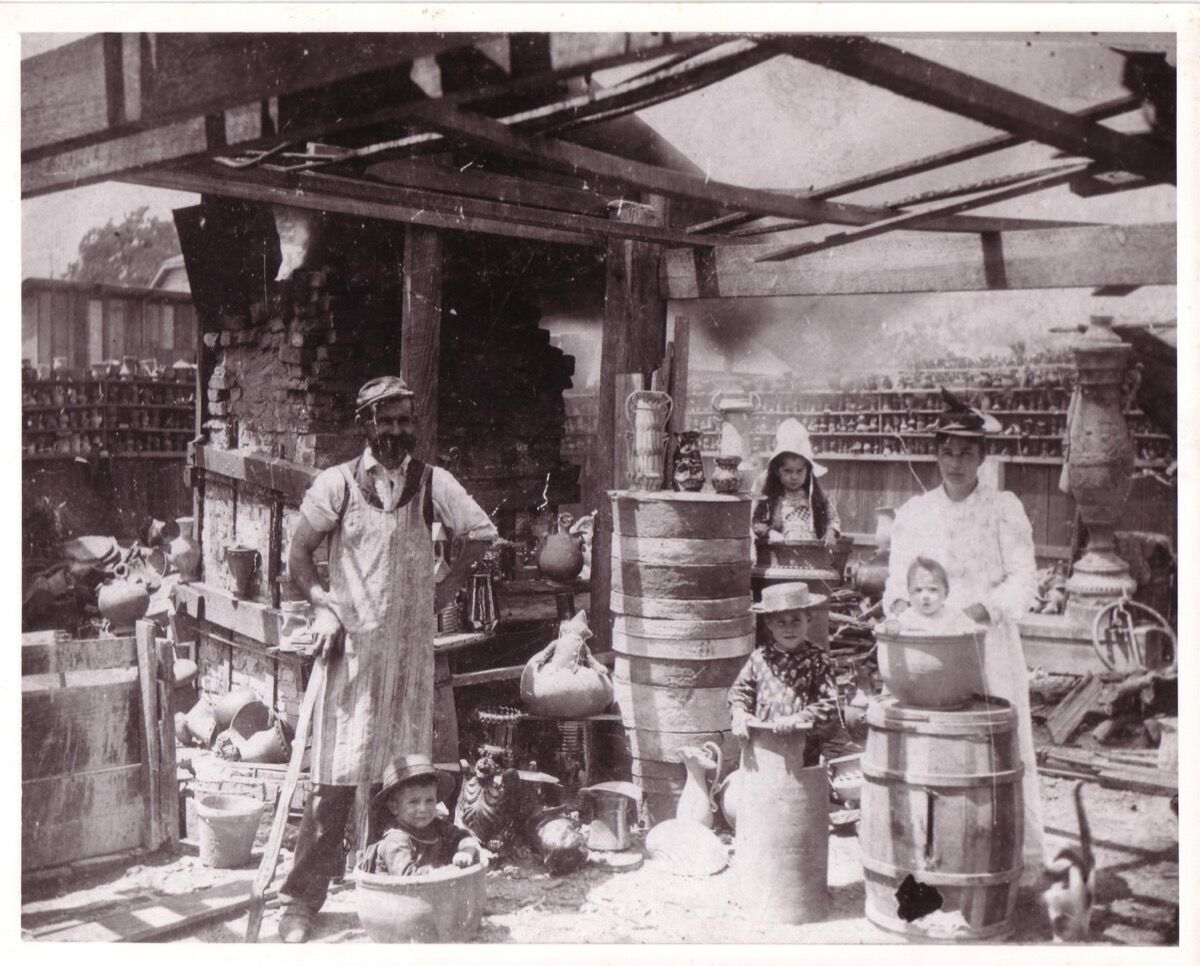

Courtesy of the Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art, Biloxi, Mississippi.

Ohr was known to cull his own red clay from the nearby Tchoutacabouffa River; he would use a barge to float it home. He created conventional, utilitarian wares, like pots and pitchers, but also chimney flues and sewage pipes. Ohr would continue to create these functional works alongside his experimental art pottery. It was the latter work that, in combination with his flamboyant personal brand, earned Ohr a reputation as an eccentric.

But what exactly made this work so notable? “He took every element of the pot and began to radicalize it,” Clark explains. For one, he embraced asymmetry, which was a bold move. “It sounds like a very simple thing, but the break with symmetry [in ceramics] didn’t really begin to happen until the 1950s,” Clark explains, “when ceramists like Peter Voulkos and others began to tear the vessel form apart and reconstruct it.” During Ohr’s time, people were accustomed to buying a vase meant to sit pretty on a mantle or hold flowers. The output of the “Mad Potter”—“town and twisted, pulled apart”—was a true break with tradition.

Ohr evinced a similar dynamism and flair when it came to his glazing process and the original recipes he concocted. With glaze, Ohr was able to elevate an ordinary teapot to art, covering it in golden yellow with plumes of cobalt blue and sprays of cherry red. “He began to treat glaze as a flowing painting on the surfaces of the pots,” Clark notes, adding that French and Japanese ceramics had achieved similar feats, but “at the end of the day, nobody was doing it as radically as he was.”

And his forms were shockingly extraordinary. Key to Ohr’s process was throwing pots to the point that the walls became thin and buckled or collapsed, leading to crumples and ribbon-like ruffles. It’s a phenomenon that most people experience when learning to throw a pot for the first time, but Ohr controlled the sensation, and used it in his favor. He also began to use handles in a novel way, attaching looping and twisting coils of clay to the sides of his urns and vases, as though he were drawing with them in mid-air, Clark notes.

George Ohr, Light-colored mottled teapot, 1895–c. 1900. Courtesy of the Collection of Marty

and Estelle Shack. Photo by Phillip Ennis.

“He was the first one to begin to deconstruct the pottery form and approach it as an artist trying to make a creative statement, and not just a beautiful pot,” Clark offers.

While critics saw the works as poorly constructed, they actually required immense control and expertise, to keep pieces from falling apart and glazes from running. To this day, Ohr’s super-thin vessel walls are legendary, a feat that few have been able to achieve since. “Ceramics is very exacting; you can play with it, but if you get things wrong, what you end up with when the kiln doors open can be pretty ugly,” Clark laughs.

So while Ohr’s vessels stood in stark contrast to contemporaneous ceramics, his prices did as well. Ohr was known for asking $25 for a pot with handles (roughly $700 today). The lofty valuation may have been because Ohr had a hard time parting with his creations, which he lovingly dubbed his “mud babies.” In 1894, after a fire that originated at the Bijou Oyster Saloon tore through Biloxi and totalled the pottery, Ohr refused to dispose of his charred pieces. He kept them, referring to them as his “killed babies.”

He got a loan and rebuilt his pottery. By this time, he’d become something of a tourist attraction. Visitors passing through Biloxi would stop by the site, advertised with its outlandish signs for “Pot-Ohr-E.” They would gawk at the ceramics, and at Ohr himself, who kept a long, twisting mustache and coiffed his hair into unusual shapes; a series of now famous self-portrait photographs have immortalized his playful, fiery energy. (Decades later, of course,

and

would similarly assume oddball personas that added intrigue to their work.)

George E. Ohr, Teapot, 1897–1900. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

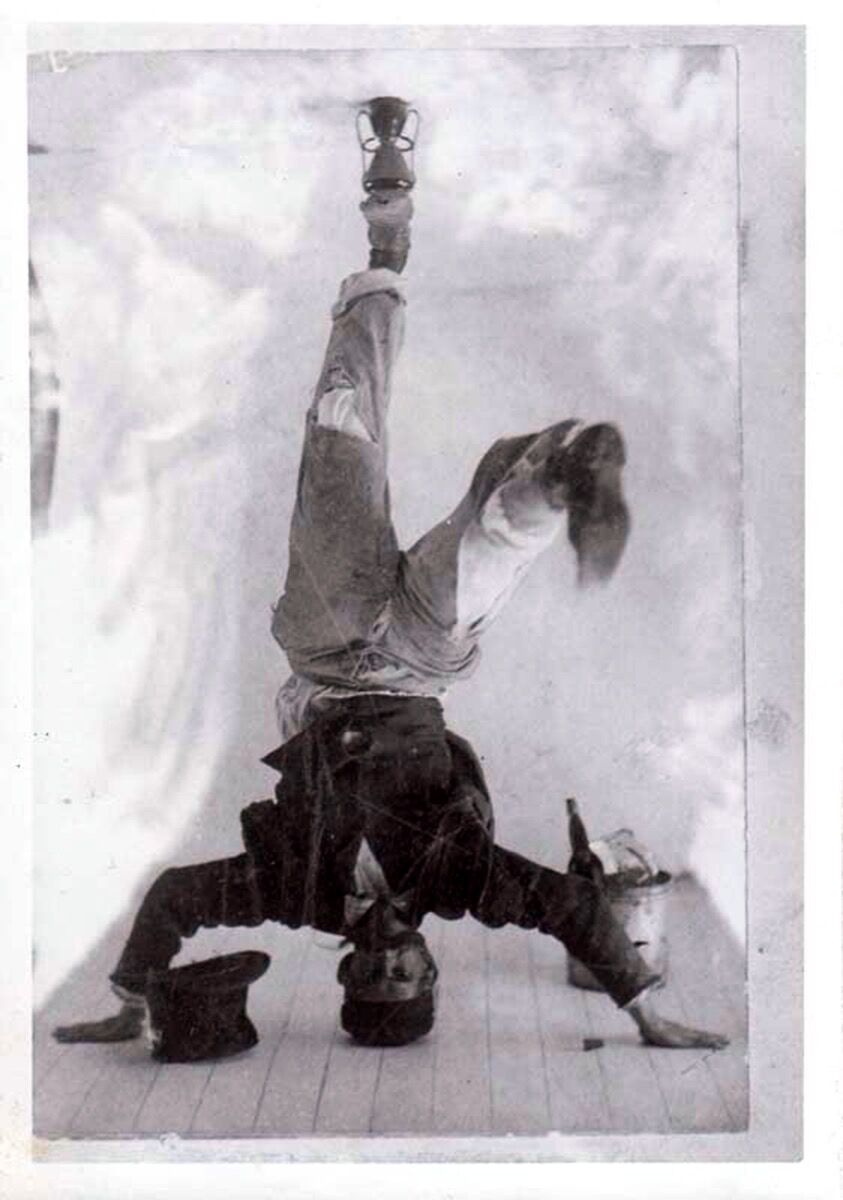

Ohr standing on his head. Courtesy of the Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art, Biloxi, Mississippi.

“All of us who’ve written about Ohr have sort of debated why he became a clown,” Clark explains. He wagers that it was at least in part Ohr’s true personality. “He was a prankster, and so when he started making work, people looked at it more as a joke than as serious art. I think that was painful for him, and the way he dealt with it was to play the clown.”

“In part it was a reaction against the rejection that he received,” Clark continues. “He could either go into a funk, or he could play up to it.” The difficulty though, was that the “Mad Potter” persona encouraged people to take Ohr less seriously as an artist.

Despite the way the public treated him, for a decade, between 1895 and 1905, Ohr was extremely prolific. He was intent on producing unique works, each with its own personality. “I am the apostle of individuality, the brother of the human race, but I must be myself and I want every vase of mine to be itself,” he once said. He submitted his works to exhibitions in New Orleans, Chicago, and Paris, but he was still met with little enthusiasm.

One of the few notes of praise came in 1901, when a publication referred tothe ceramist as “in some respects, one of the most interesting in the United States.” He won a silver medal in 1904 at the Louisiana Purchase Centennial Exhibition in St. Louis, but none of his work sold. More esteem came for his glazes, which only angered Ohr, as he considered their brilliance accidental, attributing their beauty to fire. In 1903, he stopped using glazes altogether, instead focusing on developing raw, dynamic forms.

Courtesy of the Ohr-O'Keefe Museum of Art, Biloxi, Mississippi.

Soon, rejection wore on the artist, though, and spelled his downfall. External stressors may also have played a role, including personal loss—of the 10 children he and his wife had, only six reached adulthood—and a dispute with his siblings over family land.

Ohr stopped selling off his works piece by piece, and instead, began to search for a buyer to take on thousands of wares. Believing that his practice could not be understood through single vessels, he once sent 50 pots to a museum in New Orleans; when the institution only wanted to keep a dozen, he demanded all 50 be returned. In 1909, he shuttered his pottery altogether, and stopped creating work around the same time. Then 52, Ohr lived off of an inheritance for the rest of his life; he’s said to have relished in his oddball tendencies, which included growing a long beard and riding a motorcycle on the beach. He died in 1918 of throat cancer.

His wife, Josephine, tried to sell off Ohr’s work, but was unsuccessful. The Ohr children turned the pottery into an auto shop, and held onto the collection, in a garage, for decades.

In the late 1960s, antiquing for car parts on the Gulf Coast, antiques dealer Jim Carpenter and his wife Miriam encountered the 7,000 ceramic vases, bowls, pitchers, and other vessels that Ohr had left behind. Soon after, Carpenter sought to buy the entire lot. Negotiations with the heirs went on for years; allegedly, both parties initially agreed upon the price of $50,000, but the Ohrs wagered for more. Carpenter brought the haul to New Jersey, and began to sell it off.

George Ohr, Tall dark green incised vase, 1895–c. 1900. Courtesy of the Collection of Marty and Estelle Shack. Photo by Phillip Ennis.

George Ohr, Very tall, mottled two-handled vase, 1895–c. 1900. Courtesy of the Collection of Marty and Estelle Shack. Photo by Phillip Ennis.

Scholarship and exhibitions of Ohr’s work emerged in the ’70s and ’80s; in 1978, the first solo show was held at the Mississippi State Historical Museum in Jackson, Mississippi, and books were published, like The Unknown Ohr: A Sequel to the 1973 Monograph (1986) by Robert W. Blasberg and The Mad Potter of Biloxi: The Art and Life of George E. Ohr(1989) by Garth Clark, Robert A. Ellison, Jr., and Eugene Hecht.

By the mid-1970s, the vessels had made their way into New York shops, and

and

were among early collectors. Johns even included depictions of the pots in his paintings, giving Ohr valuable art-world exposure at his Leo Castelli Gallery exhibition in 1984. Other collectors and institutions soon followed.

Nearly 90 years after Ohr’s death, the Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art, a Smithsonian affiliate institution, opened in 2010, in a gleaming $25 million Frank Gehry building. (Its name refers to former mayor of Biloxi Jeremiah O’Keefe and his late wife Annette, in whose honor he had gifted $1 million to help fund the original museum.)

Unlike Ohr, the living artists in Clark’s show, “Regarding George Ohr” at the Boca Raton Museum of Art, have seen marked success during their lifetimes, and many show with prominent

galleries. But like Ohr, many are the subject of ire among traditional ceramists. “They are all very contentious figures,” Clark offers. “The ceramics community has a very difficult time with the informality of these works.”

He points to Peter Voulkos, who gained visibility in the mid-1950s, but was attacked for his (supposedly) poorly made works, which he often made holes in. Some five decades later, Sterling Ruby was met with similar criticism. “There’s a kind of conservative expectation about ceramics,” Clark offers.

But the way that Ohr fought against the conservatism certainly played a role in paving a way for ceramic artists of present. “He was very conscious of the work and its quality; he was prescient in that he could see into the future and understand where things would be,” Clark explains.

“Ohr said that ‘eventually the nation will build a temple to my genius,’ which was very laughable at the time,” Clark adds. “And then one of the top architects in the world ends up doing that. It’s a fascinating story.”