Before I begin this piece in earnest, I think it's only fair to tell you two things. Firstly, Stoke-on-Trent is not the destination of choice for those looking to spend a weekend in picturesque surroundings. While I might have just offended the good inhabitants of the city with this statement, it has to be said that, taken as a whole, this is far from the prettiest place in England. So why visit? I'll come to that in a minute, but there's something else you should know before you pack your weekend bag. The city of Stoke-on-Trent is a modern invention, one that didn't exist before 1910. Today's city is a conglomeration of six separate towns (and a couple of villages, such as Etruria), that are collectively known as The Potteries. Individually they are Burslem, Fenton, Hanley (the city centre), Longton, Stoke and Tunstall.

Before I begin this piece in earnest, I think it's only fair to tell you two things. Firstly, Stoke-on-Trent is not the destination of choice for those looking to spend a weekend in picturesque surroundings. While I might have just offended the good inhabitants of the city with this statement, it has to be said that, taken as a whole, this is far from the prettiest place in England. So why visit? I'll come to that in a minute, but there's something else you should know before you pack your weekend bag. The city of Stoke-on-Trent is a modern invention, one that didn't exist before 1910. Today's city is a conglomeration of six separate towns (and a couple of villages, such as Etruria), that are collectively known as The Potteries. Individually they are Burslem, Fenton, Hanley (the city centre), Longton, Stoke and Tunstall.

So, why visit Stoke? Simply because (along with Ironbridge in Shropshire) it is one of the most important historical industrial sites in the world. It was here that geology; the availability of water, coal and clay combined to create the world centre of ceramic production as we know it.

History of The Potteries

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Romans and Saxons made pottery in the area, but the earliest finds date from as far back as 2,000 BC. It was the industrial revolution that began to create modern Stoke, a process finished by the politicians of the twentieth century. By 1710 the town of Burslem was well known as a pottery centre, but things really took off in 1759 when Josiah Wedgwood set up his factory there. In turn this started a trend for other well-known names to establish themselves in the 'six towns'. Josiah was not the first potter, or even the first member of his family, to produce pottery in the area, but remains the most well known. Interestingly, porcelain and bone china were not high on Wedgwood's agenda.

In the years leading up to the 17th century, European potters were desperate to learn the secrets of producing fine white porcelain, which had been a Chinese speciality. The Meissen factory in Germany is usually credited with discovering the production method, which involves the fusion of kaolin and alabaster at high temperatures. However it wasn't long before an English chemist, William Cookworthy, also determined the technique. After this, the English pottery factories (which were located around the country) experimented with the use of burned animal bones as a calcareous flux, and bone china was born. It remains a very British form of pottery, sitting alongside more rustic forms such as earthenware and stoneware.

In the years leading up to the 17th century, European potters were desperate to learn the secrets of producing fine white porcelain, which had been a Chinese speciality. The Meissen factory in Germany is usually credited with discovering the production method, which involves the fusion of kaolin and alabaster at high temperatures. However it wasn't long before an English chemist, William Cookworthy, also determined the technique. After this, the English pottery factories (which were located around the country) experimented with the use of burned animal bones as a calcareous flux, and bone china was born. It remains a very British form of pottery, sitting alongside more rustic forms such as earthenware and stoneware.

Wedgwood was quickly followed by the likes of Minton, Copeland, Spode and Ridgeway. As the popularity of pottery took off (partly fuelled by the fashionable tea trade from the East Indies), so too did the number of factories in the Potteries. By the end of the 19th century over 200 factories were operating in the area. Some manufacturers were less scrupulous than others and the copying of designs, names and symbols was widespread. Some companies had deliberately misleading names such as Vedgewood and the Dresden Porcelain Company. Even reputable companies occasionally shared resources -- Thomas Minton is widely credited with designing the famous 'Willow Pattern' for Spode before going on to found the company that bears his name. Minton was one of many companies that specialised beyond the production of ornamental pieces and tableware, becoming famous for its ceramic tiles. Another was the Twyford factory in Hanley which became leaders in the production of sanitary ware for bathrooms.

One of the reasons that production moved to the area from other areas was the loss of woodland in more rural locations like Coalbrookdale and Norwich. The availability of coal, together with ivory clay and red or blue Etruria Marl and water from the River Trent meant that manufacturers had ready access to all the resources they were likely to need, including a large labour force in the urban area.

The success of the potteries around Stoke was a double-edge sword. Ill health was widespread with diseases like 'potter's rot' caused by the use of lead glazes. At the start of the 20th century, over two thousand bottle kilns throughout the city created a permanent haze of smoke and pollution over the area. Today most of the bottle kilns have been destroyed and, when visiting the somewhat sanitised remainders, just how grim working in them would have been.

The bottle kilns themselves were as individual as their owners, with no two arrangements or designs being quite the same. The kiln consists of two main parts, the hovel, which is the outer bottle shaped structure acts as a chimney and protects the oven inside. This is the kiln itself and is known as the crown. Crowns are round and their foot-thick walls are strengthened with iron bands, known as bonts, to protect them from the forces of firing. Items to be fired were placed in fireclay boxes called saggars which were stacked to the top of the crown before the doorway (or clammins) was sealed and the fires lit.

The bottle kilns themselves were as individual as their owners, with no two arrangements or designs being quite the same. The kiln consists of two main parts, the hovel, which is the outer bottle shaped structure acts as a chimney and protects the oven inside. This is the kiln itself and is known as the crown. Crowns are round and their foot-thick walls are strengthened with iron bands, known as bonts, to protect them from the forces of firing. Items to be fired were placed in fireclay boxes called saggars which were stacked to the top of the crown before the doorway (or clammins) was sealed and the fires lit.

Bottle kilns were generally fired once a week. The first, or biscuit, firing took three days and a second firing, known as glost firing, took two. Kilns never fully cooled and the intense heat added to the dark and claustrophobic conditions in which men, known as placers, stacked and replaced the saggars into towers known as bungs. Temperature control during the firing was crucial and failure could ruin weeks of work. As well as the bottle kilns there were other specialist types of kiln, including Muffle Kilns and Calcining kilns.

In total, over 1,500 potters came and went during the area's heyday and the reality of life in the potteries and potbanks (which was though to be a more craftsman-like term than factory) is easily forgotten in a fog of nostalgia. Brian Bailey accurately described the city as "having a kind of self-congratulatory air about its prosperous past."

Not all of Stoke-on-Trent's famous sons are known for their pottery. One in particular was the novelist, playwright and essayist Arnold Bennett. He was born into an impoverished childhood in Hanley in 1867 and set many of his novels in the 'Five Towns', which are drawn from those in Stoke-on-Trent. Keen eyed readers will have noticed the reference to only five of the six towns -- for some reason he seems not to have bothered with Fenton. Many locations can be directly linked with his works, even although he changed many of the names. Shawport in the books is Longport, while Hanley became Hanbridge.

Discovering the Past

For visitors who are more interested in learning about the history of Stoke than picking up a bargain in one of the many factory shops, then the first port of call has to be the excellent Gladstone Pottery Museum in Longton. This is very much a working museum and there are plenty of opportunities to ask questions of the craftsmen, and women, as you explore 'the only remaining complete Victorian pottery factory'. As well as detailed explanations of the key stages involved in pottery production, there is an excellent exhibition about the development of the toilet, called unsurprisingly 'Flushed With Pride.'

Another museum focusing on the 'glory days' of Stoke is the Etruria Industrial Museum. Featuring Jesse Shirley's Bone and Flint Mill and located on the Caldon and Trent canals, this is an ideal compliment to the Gladstone museum. Also worth a look is The Potteries Museum and Art Gallery.

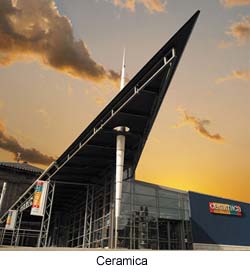

A more modern take on the areas industry and history is provided at Ceramica in Burslem, to the north. This is very much a 'hands on' experience and one that children are sure to love. In three areas, including Bizarreland, The Pavilions and the Mezzanine you can throw your own pots, take a magic carpet ride over Burslem, have a go at firing ceramics and learn about some of the most famous names in the industry.

A more modern take on the areas industry and history is provided at Ceramica in Burslem, to the north. This is very much a 'hands on' experience and one that children are sure to love. In three areas, including Bizarreland, The Pavilions and the Mezzanine you can throw your own pots, take a magic carpet ride over Burslem, have a go at firing ceramics and learn about some of the most famous names in the industry.

Some of the potteries themselves feature very good museums in addition to their other facilities with the most well known being the Spode and Wedgwood visitor centres and the Dudson Museum. Dudson are the 'oldest surviving family business in the ceramic tableware industry.' Admission to the small museum is free, and features include the bottle oven in the original factory courtyard, where you will find a collection of Dudson pottery from the firm's two-hundred year history. The museum is located in Hanley, right in the city centre, making it ideal for combining with a shopping trip or excursion to the Cultural Quarter.

For an antidote to the pottery industry visit Ford Green Hall. This beautiful black and white timber building contains a number of contemporary collections and allows visitors to 'experience the seventeenth century at close quarters.' The gardens were planted in 1996 to reflect the gardening styles of the 1600s when the hall was built and include two knot gardens and low hedges that mirror the design of the hall's timbers. The gardens are open throughout the year and admission is free, while the hall itself is covered by the council's Passport Scheme (see below).

Modern Stoke

Pottery is still at the heart of the modern tourist industry in the area and visitors should look out for the leaflets which provide details of the Ceramic attractions in the area. These are widely available, but can also be picked up from the Stoke-on-Trent Touristy Information Centre in Hanley.

Pottery is still at the heart of the modern tourist industry in the area and visitors should look out for the leaflets which provide details of the Ceramic attractions in the area. These are widely available, but can also be picked up from the Stoke-on-Trent Touristy Information Centre in Hanley.

Things to remember when planning any visits include the Factory Holidays. Details of these dates are available from Tourist Information, and while most factory shops and museums remain open, many factory tours will not be available. As always, if in doubt, check with the company in question. It's worth noting that some manufacturers have more than one shop in different parts of the city, and that some shops sell different items to others. For example, ceramic collectors will love the full price wares on offer at Royale Stratford and Moorcroft, while seconds and 'utility' quality items are available from many sources. Some makers, such as Portmeirion, have several shops and separate 'clearance outlets'.

Bridgwater and Royal Stafford have so-called pottery cafes where children and adults can try their hand at decorating blank pieces and many factories offer visitor tours of one sort or another, although some are more frequent than others and some need to be pre-booked.

Getting There & Getting Around

The nearest airports are Manchester, Nottingham (East Midlands) and Birmingham, while the city is linked to the motorway network and the M6 by good main roads. Although the city has a mainline railway station, it is quite a way from Hanley and the City Centre. The distance between the furthest attractions is as much as eleven miles, and the factory shops and museums dotted about the towns mean that a car is really essential.

It's also useful to note that, like many other areas in the UK, the four museums that are operated by the City Council (Gladstone Pottery Museum, The Potteries Museum and Art Gallery, Ford Green Hall, and Etruria Industrial Museum) operate a combined 'passport' ticket which offers unlimited return visits within a year and qualifies holders for a discount at some other attractions.

Other nearby Attractions

Stoke's central location in the west midlands makes it an ideal base to explore further. To the north-east, the Peak District National Park is only ten miles away, with numerous attractions including the Chatsworth estate. Britain's most famous theme park, Alton Towers is also nearby, as are the exciting gardens of Bidulph Grange (owned by the National Trust) and Trentham Gardens, which have recently undergone major refurbishment. More Information:

We regret that we no longer have the resources to maintain up-to-date links and/or hours and pricing details for the various sites and attractions listed on this website. For more information about the location(s) listed above, please use your favorite search engine or visit Wikipedia.

Richard Crowhurst is a freelance writer and author based in Lincolshire, England. He writes on many subjects, including history and heritage topics. More details can be found on his website, http://www.freelance-writer-and-author.co.uk