By Melinda Farkasdy

In the Summer of 2020, an extraordinary ceramics exhibition took place at the FISE Gallery in Budapest1. The event was the debut of a recently formed community of young Hungarian ceramicists, Criminal Craft2. The showcased works (from busts to vases and plastic arts) revealed a telling shift away from traditional, function-based potteries towards an emphasised application of sculptural-artistic approaches.

Due to the community’s manifesto, the members try to find a new visual language for ceramics, exploring overlaps between art, design and handicraft. They state that it is unnecessary to distinguish these categories, indeed, the fusion of the terms is an opportunity not a difficulty for a ceramicist. Ceramics itself and their favoured wood fired method are the mere stabile points in their work, aside from these it is useless to maintain outworn contexts and homogenous territories. Instead of the technical skills, the main attention is on the treatment of the material, perceived as a kind of medium by the members. In their name,’Criminal’ refers to an experimenter intention, i.e. to diverge from traditional ceramic objects and create pieces closer to fine art. However, the noun ’Craft’ is the attribute of their activity. Criminal Craft declares that the term ’Artist’ has lost its original meaning over time hence they conditioned to miss it out from their name3.

At first reading, this directive might seem a bit contradictious and precarious. Artistic approach but the categorical omission of the term Artist or Art from the community’s name? No need to separate categories but the unequivocal will to make sculptural objects instead of functional, traditional ceramics? On the other hand, if we pore over the statements outlined above, we receive a much more clarified statement.

Ágnes Nagy-György

András Zsigó

Boglárka Nagy

Bernadett Furó

Eszter Sághy

Criminal Craft members form the new generation of the Hungarian ceramicists (graduated this year or in the last few years). As adventurous creatives at the beginning of their career, they aimed to strengthen and reshape the community of professional ceramicists in Hungary: to encourage collaborations, launch discussions (even with representatives of other creative professions) and inspire young ceramicists to stay in their discipline4. Constituting a community and working in a collective is quite a rare phenomenon in the history of (Hungarian) ceramics. Although there were a few predecessors, it is not particular to this field. Even though Criminal Craft members still stick to their artistic attitude, thus uniformity is far from a criterion, and they prefer the label ’community’ to ’team’ or ’group’5, they decided to join each other and develop togetherness. Before we provide a possible interpretation in this regard, it is worth to take a step back and analyze current discourses and receptions of Craft.

Recent studies on contemporary craft culture often discuss the fluidity of the term and its tight relationship with design and art (and even further areas). What is more, the actual perception of Craft enables us to examine it as a kind of value found in non-traditional craft contexts6 as well, such as the wide range of DIY activities7. When Criminal Craft declares that the term ’Artist’ has lost its original status, they principally imply it to the amateur makers, who popularize their products on several social media platforms and introduce themselves as self-taught artists. The ’Criminals’ recognize the efforts and enthusiasm of these ’artists’, at the same time, they are also aware that the DIY tag opens the door to superficial yet ambitious creators, whose works might appear equivalent to theirs from the perspective of a laic spectator8. In this sense, we consider that Criminal Craft does not query what Adamson states on craft values, located in ’hand-built’ or ’artisanal’ pieces9, indeed, we explain this approach as a kind of safeguarding of interests – not as an elitist, derogatory manner. It proves the fact that the ceramicists felt advisable to form a community and represent their mindset by the power of collective effort.

Looking over the history of independent craft communities in Hungary, it can be noticed that a greater part was a collective of multiple craft genres10. An exception to this is the still existing DeForma Group. Formed in 1993, DeForma members decided to pursue an activity in porcelain, to research relations between fine art and decorative art as well as to contribute to the renewal of applied ceramics11. Criminal Craft regard DeForma as their straight predecessor12, however, the main difference between the two collectives is demonstrable: DeForma members had been already experienced designers, artists and craft makers in the year of the foundation13, while Criminal Craft members are career-entrants. It is telling that DeForma founder, Éva Kádasi taught Criminal Craft members at university, and she is still their spiritual mentor. Kádasi tutors the community’s ambitious enterprise, the construction of a wood fired kiln in Zebegény (North-Hungary). This project enters a new chapter in Criminal Craft’s life as the collective lefts Verőce, where their first ceramics were made14. Verőce played an important role during the ’Criminals’ university studies and defined the first steps of their career path. The tiny, picturesque village near Budapest hosts the Gorka Ceramics Museum (Gorka Kerámiamúzeum), whose garden gives place to a two-chamber wood fired kiln. The kiln was built by Éva Kádasi and her students in 2013, and it belongs to the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design (MOME)15. Gorka Ceramics Museum displays artworks of the denominator Hungarian ceramicist family, presenting pieces by the three generations on permanent view16. It is no wonder that the Museum’s outstanding collection influenced Criminal Craft, thanks to fruitful symposiums in honour of Géza Gorka and his daughter, Lívia. By the occasion of these events, the Museum requested the ’Criminals’ to reflect on the œuvre of the great masters and create pieces in their spirit. The newborn ceramics were exhibited in the Museum’s hall, amidst the Gorka ceramics, drawing interesting liaisons between past and present. Besides the symposiums shaped the skills of the members, encouraging them to deploy their creativity, they also offered a good opportunity to examine ceramics traditions and get inspiration from former tendencies.

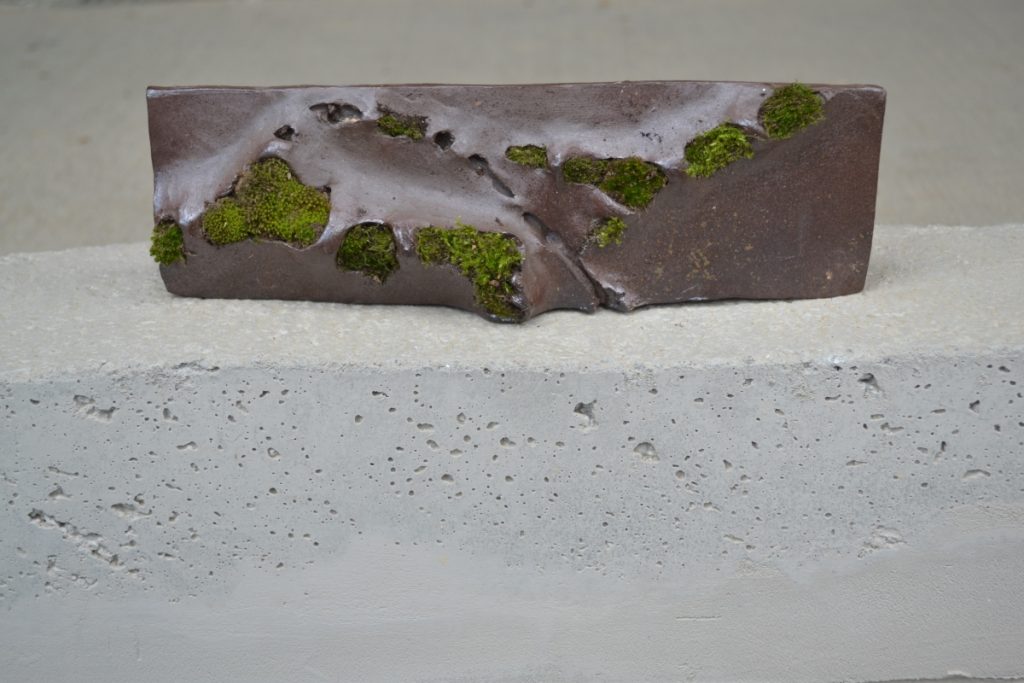

At this point, we must dwell on the significance of wood firing in Criminal Craft’s work. It shall be born in mind that although wood firing is a common method in the field of ceramics, it is also a kind of attitude. Originated in the Far East, established in Europe by Bernard Leach in the first half of the 20th century, the wood firing became an essential part of the so-called studio pottery movement all over the world17. The aesthetic values of wood firing, such as the particular patina of the flowing prints of fire, add some spontaneity to these ceramics. Many times, the final result can not be predicted for sure thus the process ends in suspense. Though sculptural, artistic attempts can be realized in electronic or gas-fired kilns as well, the sometimes unforeseeable elements of wood firing might be more appropriate for experimental, sculptural ceramic-making.

This idea takes us back to the artistic approaches of Criminal Craft. So far, we deliberately evited to brood over the question: do they commit to art, or do they belong to craft anyway? Critical writings on ceramics bring forward the dilemma again and again, and the perception of ceramic objects varies throughout history. We presume that this kind of controversial assertions to the art status of ceramics leads us nowhere. Instead, we should focus on the constantly changing relationship of a ceramicist to function, industry, material, and the needs of their time. Criminal Craft decided not to fall into line with ephemeral trends, but rather to search for new visual languages and responsibly polish public taste. Their intention suggests us to look underneath the surface and launch dialogues on 21st century-demands. By this time, the emancipation of Craft has eventuated its revaluation, cultivating the reinvestment of individual, conceptual ceramics. It may not be prognosticated what this will mean for the future, especially in the Hungarian cultural context. However, the recognition of the gap between amateur and professional, flaw and artistic, the urge to form a community of progressive makers heralds the comeback of an acquainted phenomenon: sculptural values in clay.

You can follow the Criminal Craft community on Facebook and Instagram.

Melinda Farkasdy is art historian at the Museum of Applied Arts, Budapest, Hungary.