Balcony view of The Met Fifth Avenue's Great Hall. Photo by the author

The Departments of Islamic Art and Asian Art often work together to illustrate the overlap between our respective collections and to display related material together. In order to see these connections up close and personal, I recently took a stroll across the balcony above the Great Hall and found some fascinating links between ceramics made in China and those made in the Islamic world.

Left: Ewer, late 7th century. Chinese, Tang dynasty (618–907). Earthenware with three-color (sancai) glaze; H. 11 1/8 in. (28.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Stanley Herzman, in memory of Gladys Herzman, 1997 (1997.1.2). Top right: Bowl with green, yellow, and brown splash decoration, 10th century. Iran, Nishapur. Islamic. Earthenware; white slip, incised and splashed with polychrome glazes under transparent glaze (sgraffito ware); H. 2 7/8 in. (7.3 cm), Diam. 10 1/4 in. (26 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1938 (38.40.137). Bottom right: Bowl, 12th–13th century. Byzantine. Earthenware, glazed (mezzo-maiolica); Overall: 3 7/8 x 9 1/16 in. (9.9 x 23 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1910 (10.15.1)

The story beings in seventh-century China, during the Tang dynasty (618–907), when sancai (three color) funerary wares were popular productions, such as the ewer seen above (left), which is itself an Iranian form. Making their way across the Silk Road, these amber, brown, and green lead-glazed wares served as inspiration to craftsmen in Iran, and a nearby bowl highlights a 10th-century copy of this style (above, top right), made in Nishapur and known as "splash ware."

The artist of the Nishapur bowl has included an innovative sgraffito (incised) pattern into the body of the clay using both geometric and floral forms. A third object displayed with this group, from 12–13th-century Byzantium (above, bottom right), illustrates the further spread of this style, some 500 years and thousands of miles from its origin. Evidently this glaze had a timelessness to it!

Left: Bowl, 7th century. Chinese, Sui (581–618)–Tang (618–907) dynasty. Porcelain with white glaze; H. 3 1/4 in. (8.3 cm); Diam. 4 1/2 in. (11.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Charlotte C. and John C. Weber Collection, Gift of Charlotte C. and John C. Weber, 1994 (1994.605.45) Right: Bowl emulating Chinese stoneware, 9th century. Iraq, probably Basra. Islamic. Earthenware; painted in blue on opaque white glaze; H. 2 3/8 in. (6 cm), Diam. 8 in. (20.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1963 (63.159.4)

At the same time, artisans in China were producing porcelain—the most coveted and most technically advanced ceramic in the world. Porcelain was made with kaolin clay, a substance unique to China in this period, which was found near Jingdezhen, a great ceramic-producing city. When fired at an extremely high temperature, kaolin clay transformed into a very fine, hard, semi-translucent white ceramic that local collectors coveted and remained in high demand as a trade object. Potters in Basra, Iraq, attempted to emulate the beauty of this pure white color, but without access to the naturally occurring kaolin clay, potters had to improvise and instead chose a white slip (liquefied suspension of clay particles in water) to cover the ceramic body. Some objects from this period, as in the bowl above (right), were embellished with a cobalt blue design.

Given the back and forth of shape and style across the Silk Road, is it possible these ninth-century cobalt-and-white Basra ceramics inspired the famous blue-and-white wares made in China during the Yuan dynasty? We cannot know for sure, and scholars have varying opinions, but blue-and-white Chinese porcelain was a very popular collector's item in the Islamic world for shahs and sultans, and served as inspiration for ceramicists working in Iznik, Turkey, as well as various cities in Iran. On these sites, artists made imitation blue-and-white ware of excellent quality, both for the local market as well as for export to other parts of Asia.

Left: Bottle with peony scroll, mid-14th century. Chinese, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). Porcelain painted with cobalt blue under a transparent glaze (Jingdezhen ware), H. 17 1/2 in. (44.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1926 (26.271.1a, b). Top right: Plate with grapes, ca. 1570. Turkey, Iznik. Islamic. Stonepaste; polychrome painted under transparent glaze; H. 2 7/8 in. (7.3 cm), Diam. 14 1/4 in. (36.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891 (91.1.102). Bottom right: Imitation blue-and-white bowl, 17th century. Iran, possibly Mashhad. Islamic. Stonepaste; painted in blue under transparent glaze; 7 1/2 x 14 1/4 in. (19.1 x 36.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Nellie Kuh, by exchange, Louis V. Bell Fund, and funds from various donors, 1967 (67.108)

Other displays continue this story inside the Islamic Art galleries. In gallery 455, a display case highlights the styles and motifs that became popular in Iran during the Mongol Ilkhanid Period (1206–1353). Potters in Iran imitated Chinese glazes, such as the bright-green celadon wares shown below, both of which feature ornaments with small fish swimming in the sea-colored glaze.

View of display case in gallery 455 showing a bowl created during China's Southern Song dynasty (bottom left) and a bowl with fish motifs from 14th-century Iran (right). Photo by the author

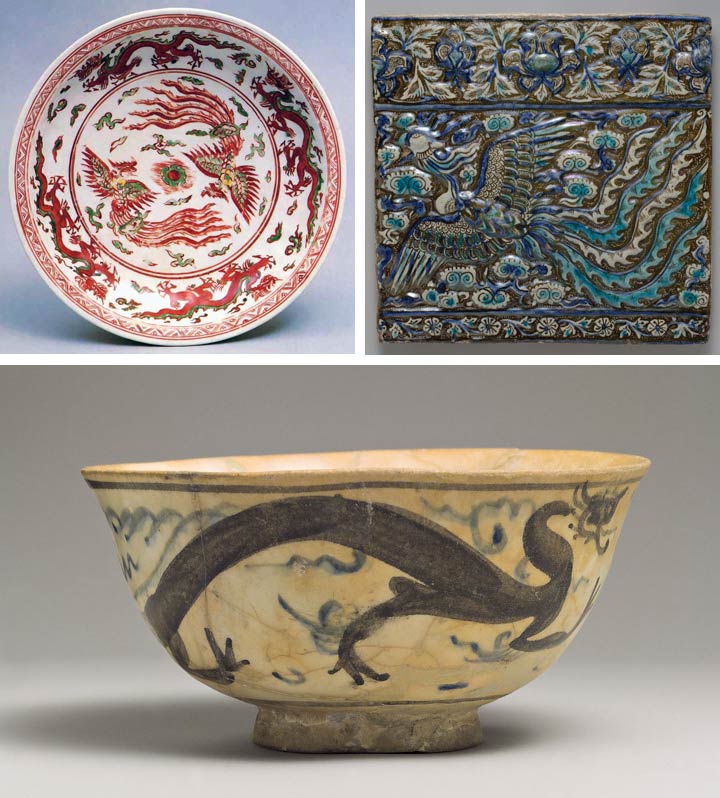

And Chinese decorative motifs, such as the dragon and mythical phoenix bird (known in China as the fenghuang) started appearing on all kinds of Iranian decorative arts, especially ceramics. If you don't look at the labels, it can be very difficult to tell between the Chinese and Iranian pieces!

Top left: Dish with phoenixes and dragons, 16th century. Chinese, Ming dynasty (1644–1368), probably Jiajing period (1522–66). Porcelain painted with colored enamels over transparent glaze (Jingdezhen ware); Diam. 12 in. (30.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Richard E. Linburn, 1981 (1981.368.2). Top right: Tile with image of phoenix, late 13th century. Iran, probably Takht-i Sulaiman. Islamic. Stonepaste; modeled, underglaze painted in blue and turquoise, luster-painted on opaque white ground; H. 14 3/4 in. (37.5 cm), W. 14 1/4 in. (36.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1912 (12.49.4). Bottom: Bowl, 15th century. Iran or Central Asia. Islamic. Stonepaste; painted in blue and black under transparent glaze; H. 2 15/16 in. (7.5 cm), Diam. 5 7/8 in. (14.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, V. Everit Macy Gift, 1932 (32.33)

For more examples of the interactions between Chinese and Islamic style ceramics, be sure to see the newly opened exhibition Global by Design: Chinese Ceramics from the R. Albuquerque Collection, which expands upon this story by tracing the influence of these wares in Europe and the Americas.

Related Links

RumiNations: "Unravelling the Hidden Production History of Sgraffito Ware from Nishapur" (September 8, 2015)

Global by Design: Chinese Ceramics from the R. Albuquerque Collection, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through August 7, 2016

Departments: Islamic Art, Asian Art

Tags: ceramic, China, Iran, porcelain

Comments / 3 comments

Sinta Wiranata

December 21, 2018

There are many kinds of ceramics throughout the world. Various country like China, Japan, Korea. Maybe some other countries have ceramics in their history. But I only studied the three countries. this is very fun if you learn about art.

Amir Mohtashemi

March 12, 2019

Thank you, Courtney, for Shedding light on the development of Ceramics in the age of Silk route specifically the unique Porcelain type.

Craig

April 25, 2019

Great article! Very interesting read as well as informative!